34th ESPU Congress in Naples, Italy

S10: MY WORST COMPLICATION

Moderators: Gianantonio Manzoni (Italy)ESPU Meeting on Thursday 18, April 2024, 14:20 - 14:50

14:20 - 14:24

S10-1 (MWCP)

BLADDER INJURY AFTER LAPAROSCOPIC ASSISTED ORCHIDOPEXY

Luis H. BRAGA

McMaster University - McMaster Children's Hospital, Department of Surgery / Urology, Hamilton, CANADA

ABSTRACT

This is a case of a 2nd stage laparoscopic orchidopexy for a very high intra-abdominal testicle (1st stage done at another institution). Due to the high intra-abdominal location of the testicle, the gubernaculum was not available, as the internal inguinal ring was closed, and the inguinal canal could not be used as a pathway for testicular descent, as normally done in our institution. In cases where a straighter and shorter pathway into the scrotum is required, my preference is to go medially to the inferior epigastric vessels but laterally to the obliterated umbilical artery. As the testicle was located 6 cm from the internal inguinal ring, there was a concern whether it would be able to reach the scrotum. Therefore, a decision was made to bring the testicle medially to the obliterated umbilical artery to shorten even more the testicular descent pathway.

This new pathway for testicular descent was developed by introducing a 5-mm laparoscopic grasper between the bladder and the obliterated umbilical artery from the scrotum into the abdominal cavity under direct laparoscopic vision. As a safeguard to make sure there was no bladder wall injury, the bladder was filled with saline intra-operatively twice and no leak was observed. We then proceeded to fix the right testicle in the scrotum in the usual fashion, closed the ports, and discharged the patient home.

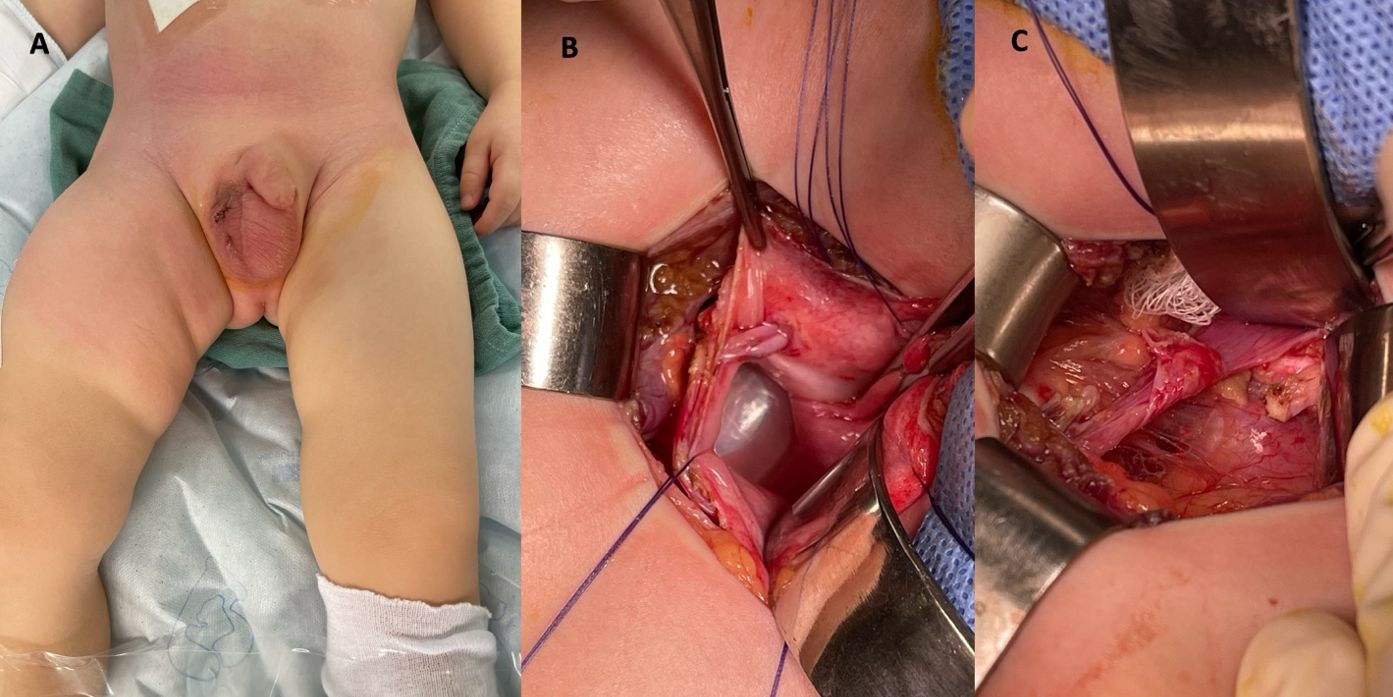

The child returned the following day with lower abdominal pain, lack of appetite, vomiting and low urine output. On physical exam, we found swelling, induration, and redness in the scrotal, inguinal, and suprapubic regions (Figure A). An urgent ultrasound showed thickening of the right spermatic cord with hematoma in the right hemi-scrotum, with no intra-peritoneal fluid collection. A CT cystogram to rule out bladder perforation was ordered and showed no urine extravasation.

Despite having negative diagnostic imaging modalities searching for intra-abdominal collection, and due to a high suspicion of bladder injury, a decision was made to take the child to the operating room for surgical exploration. A Pfannenstiel incision was done to gain access to the peri-vesical space, allowing identification of the spermatic cord which was seen going through the bladder (in and out through the lateral wall of the bladder), explaining why there was no intra-operative urine leak, no intra-abdominal collection on ultrasound, and no urine extravasation on CT cystogram (Figure B). The bladder wall was opened and the cord freed and re-routed into the scrotum. (Figure C). The child developed postoperative ileus, probably from a small amount of urine that had trickled down into the abdominal cavity before surgical exploration. He recovered completely and the 8-week follow-up ultrasound showed a viable and well-positioned right testicle in the scrotum.

LEARNING POINTS

1. The pathway for the intra-abdominal testicle should always be between the obliterated umbilical artery and the inferior epigastric artery to minimize or negate any potential risk of bladder injury.

2. If a trocar is introduced from the scrotum into the abdominal cavity to create the new pathway for testicular descent, it should be done with a full bladder to easily identify the lateral contour of the bladder wall, as an empty bladder may not be properly visualized and may be easily displaced by the trocar insertion.

3. In cases of strong suspicion of bladder wall injury during laparoscopic orchidopexy, injection of methylene blue in the bladder may delineate a very small leak that may not be very noticeable at first.

4. When in doubt, exploration of these cases should be done without hesitation, as it can establish (confirm) the diagnosis, avoiding delayed intervention in a patient who can get really sick with peritonitis due to urine extravasation.

FIGURES

Figure A shows redness in the suprapubic, inguinal and scrotal region.

Figure B shows an open bladder with a foley catheter and the spermatic cord going through the lateral bladder wall.

Figure C shows the bladder retracted medially and the re-routed spermatic cord going into the scrotum.

14:24 - 14:28

S10-2 (MWCP)

RECTAL PERFORATION AS A LATE COMPLICATION OF PROACT BALLOON IMPLANTATION IN A 8 YEAR OLD CHILD

T. LOUBERSAC 1, M.A. PERROUIN-VERBE 2, F. SADONES 3, S. DE NAPOLI 1, L. VIDAL 4 and M.D. LECLAIR 1

1) University Hospital of Nantes, Paediatric Surgery & Urology, Nantes, FRANCE - 2) University Hospital of Nantes, Urology, Nantes, FRANCE - 3) University Hospital of Nantes, Paediatric Radiology, Nantes, FRANCE - 4) Centrale Nantes Nantes Université, GeM CNRS UMR 6183, Nantes, FRANCE

INTRODUCTION & OBJECTIVES

Surgical approaches to severe urinary incontinence in neurogenic sphincter insufficiency include artificial urinary sphincters, bulking agents, urethral sling, and ProACT device (Uromedica). Previously reported complications of the ProACT procedure include balloon rupture and dislodgement, bladder and urethral erosion and perforation. We report a case of rectal perforation as a late complication of the ProACT procedure for neurogenic sphincter insufficiency(IS) and anorectal malformation(ARM).

MATERIALS & METHODS

The patient was an 8-year-old boy with VACTER syndrome, with ARM treated in infancy requiring transanal irrigation, and sacral agenesis with neurogenic bladder. Low compliance neurogenic bladder was initially treated with bladder augmentation and Mitrofanoff in 2021. Persistence of severe urinary stress incontinence led to implantation of Pro-ACT-balloon.

RESULTS

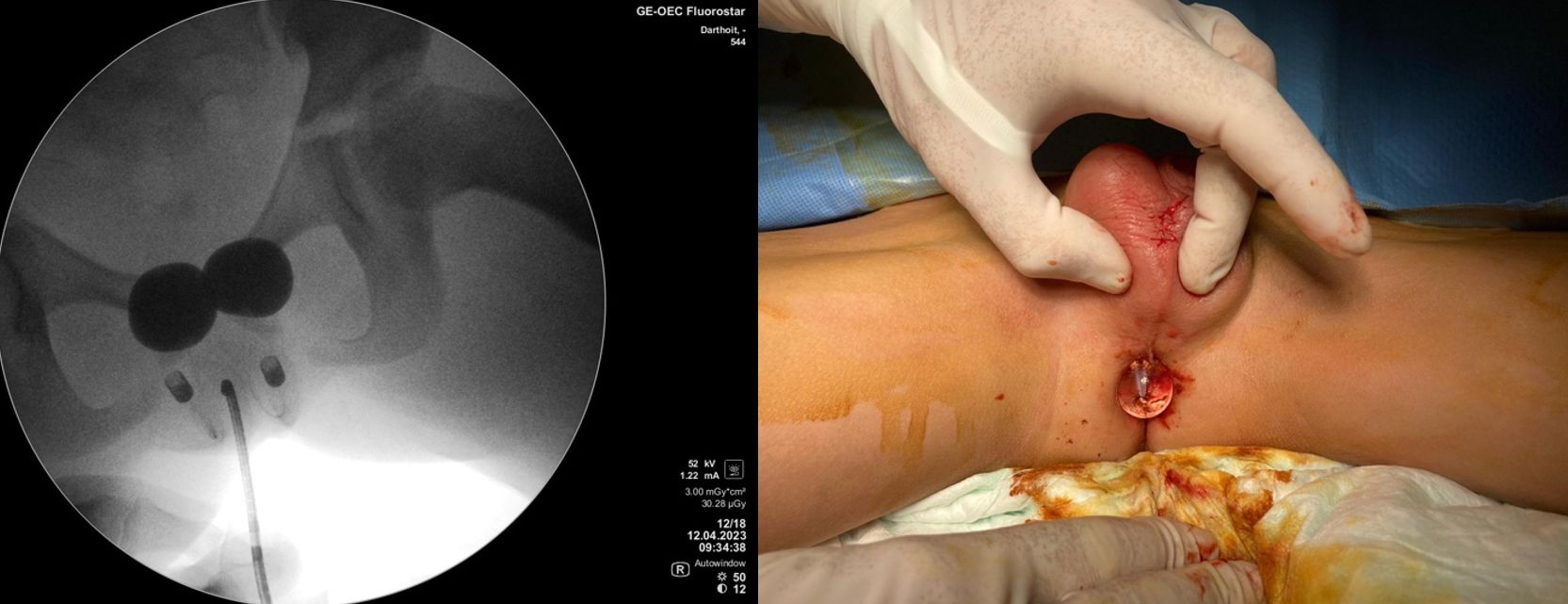

Balloon implantation was performed using fluoroscopic and antegrade endoscopic. Two Pro-ACT-balloons were placed paraurethrally below the bladder-neck through subscrotal percutaneous approach. Continence improved after 3 fillings up to 3,6ml. Nine months later, the child presented with rectal erosion and scrotal infection, which required balloon explantation under general anaesthesia and 7 days antibiotics.

CONCLUSIONS

We hypothesised that transanal irrigation would lead to rectal balloon erosion due to repeated minimal rectal trauma. To our knowledge, this complication has not been previously described in children.

14:28 - 14:32

S10-3 (MWCP)

SALVAGING A KIDNEY MAY NOT ALWAYS BE THE BEST OPTION

Sajid SULTAN

Sindh Institute of Urology & Transplantation, Paediatric Urology, Karachi, PAKISTAN

ABSTRACT

Six year old boy presented with intermittent fever for two months and left flank pain with burning micturition for a month. U/S KUB and DMSA scan showed a parenchymal collection in the left kidney with 27% function. Rt kidney was normal.

During surgery purulent infective necrotic lesion involving lower half of the kidney, the pelvis and upper ureter were removed and sent for routine histopathology. No frozen sections were obtained.

The upper half of the kidney was healthy and was salvaged. An uretero-calicostomy with closure of open calyx was performed with an omental wrap.

Histopathology reported invasive mucormycosis.

Amphotericin B was started and the kidney re-explored. Frozen sections were sent this time which showed mucormycosis in omental tissue therefore complete surgical excision of remaining renal tissue was performed including involved omentum.

Postoperative recovery uneventful. Patient later developed Amphoreticin B induced pancreatitis which was managed conservatively.

Patient was lost to follow up for two years. Recent outpatient visit showed healthy recovery with normal BMI and normal right kidney function with no left renal bed recurrence.

Renal mucormycosis in an immunocompetent child is very rare. This case highlights the importance of sending frozen sections in a purulent necrotic lesion.

14:32 - 14:36

S10-4 (MWCP)

INTESTINAL VOLVULUS BECAUSE OF CONTINENT STOMA

Seppo TASKINEN

Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, FINLAND

ABSTRACT

A myelomeningocele patient was on anticholinergic medication and the CIC program. Previously he had undergone an ACE operation. Because of difficulties in performing CIC on a wheelchair, a continent spiral Monti operation was performed at the age of 16 years. Four months later he was operated on because of intestinal obstruction. Two years later he was operated on because of intestinal volvulus around the vascular pedicle in another hospital by adult surgeons. The patient was remitted back to the pediatric hospital because the risk for recurrent volvulus. The family was worried and asked for a solution to the problem, even if the continent stoma had to be removed. In the operation, the vascular pedicle's location prevented its hiding. On the other hand, the location of the spiral Monti was completely retroperitoneal. It was decided to rely on the collateral blood supply and the vascular pedicle was ligated. In the four-month follow-up spiral, Monti is still working well.

In rare cases, the vascular pedicle of the continent stoma can lead to life-threatening intestinal volvulus. Our case indicates that at least in some cases collateral blood supply may be sufficient for continent stoma if the vascular pedicle must be transected.

14:36 - 14:50

Discussion